Language, Literature and Leadership

A blog to share reflections and resources on English teaching and Educational Leadership.

The power of ‘Everybody Writes’ (on paper!)

I’m going to start this blog post (my first in a LONG time) with a controversial statement…

I’m not a fan of mini-whiteboards.

I know, I know. They have their merits. I can accept that. And I agree! I’ve read some wonderful blog posts of late that demonstrate just how valuable MWBs can be. And I’m not arguing against that.

However, what I have found, from personal experience, is that they also have their drawbacks. To name a few:

- The seemingly endless financial cost of replacing pens, erasers, and sometimes even the whiteboards themselves – multiple times a year

- The organisational admin of constantly checking that equipment hasn’t gone walkabout

- The time you must invest in developing the routines in the first place – time that can be invested elsewhere…

- The distraction they can cause for some students if they are left on the desks throughout the lesson (is that child at the back creating the next Mona Lisa in erasable marker whilst you passionately articulate Priestley’s views on socialism? Possibly.)

The above considerations are exacerbated for me due to having a department with a lot of trainee teachers and ECTs (almost 50%). MWBs just seem to present a host of extra challenges and, in some ways, more pitfalls than perks.

And, again, whilst I fully accept that MWBs have their advantages, I also think there are some valuable alternatives.

For me, one such alternative is ‘Everybody Writes’ (on paper). The term ‘Everybody Writes’ is one of the strategies presented in Doug Lemov’s ‘Teach Like a Champion’. Lemov posits that this strategy: supports students to think more deeply; encourages students to produce higher-quality writing; boosts the thinking- and participation-ratios in the classroom.

Of course, ‘Everybody Writes’ does not dictate that students’ writing MUST be completed on paper rather than MWBs. However, for me, this is personal preference. Below I outline the reasons why.

Firstly, we have historically had issues (and therefore our past outcomes) with student resilience – particularly their writing resilience, and particularly in English. One of the most impactful things we’ve put into place is increasing opportunities in lessons for short bursts of independent practice. Previously, we’ve struggled to make time for independent practice. We constantly seemed to be aiming for the ever-elusive ‘paragraph or more’ by the end of the lesson, and were constantly falling short – meaning opportunities for independent writing were few and far between. When we moved to prioritising short bursts of independent practice, students’ confidence seemed to transform. Instead of seeing writing in English as an insurmountable task, we gradually fostered students’ resilience by exposing them to opportunities to write independently in every lesson, with length varying from a sentence to a whole essay, depending on the lesson/task.

Another point on the same lines that I want to address: student attitudes to English. Five years ago, student perceptions of English were dire. It felt like we were hearing the same feedback from students over and over again: they loved Maths, they felt successful in Maths, Maths made them feel good. The reverse was true for English. When we delved into this, it seemed to come down to the opportunities students were provided to feel successful. In Maths, they could practise an equation, quickly check it was correct, and then move on. A short burst of independent practice was rewarded by instant reinforcement that they were doing the right thing. In English, however, they weren’t given the same opportunities. Often, they were expected to write a paragraph or more, and they would spend the whole task in a state of apprehension and confusion, not knowing if they were getting it right or not. Through introducing short bursts of independent writing with Everybody Writes (on paper) - along with, to be fair, other things such as strategic multiple-choice questions - we were able to change students’ mindsets. They were given more opportunities to feel successful.

Now, of course, there is the argument that if students are writing a sentence or two, they can just do it on a MWB. True! But, for us, there seemed to be a bit of mental barrier for children. Writing on a MWB was low stakes, low pressure, low threat. Then when it came to writing on paper, they were crumbling, seeing it as too challenging and too daunting. By getting students used to writing on paper, we overcame the notion that doing so is ‘scary’. In essence, we created a culture in which writing on paper became as low threat – in fact, it is a valuable opportunity to receive feedback and have misconceptions be addressed. Which leads me to my next point.

Purposeful circulation and live marking are cornerstones of our assessment policy in English. We prioritise live marking because we know it is a high-leverage feedback method, and it because it supports teachers’ marking workload. However, the impact of live marking can be impeded if students aren’t being given regular opportunities to write: you can’t live mark something that hasn’t been written! Therefore, we found when we introduced more Everybody Writes (on paper) we were given more opportunities to provide students with meaningful feedback. And with this feedback being in their books, rather than on MWBs, they also had it to refer back to later on.

Finally, Year 11 outcomes. Our outcomes in English have gone a progress score of less than negative 1 in 2019 to having a positive progress score (for the first time ever!) in 2024. There are many things we did to achieve this (see other blog posts I have written such as Strategic Do Now tasks and Improving analysis). However, the aforementioned considerations around writing resilience, opportunities for feedback, etc. have all greatly contributed, too. Therefore, I would assert that Everybody Writes (on paper’) has been contributed to our improved outcomes. In a Year 11 class, this strategy provides the perfect opportunity to rehearse shorter tasks that reflect some of the smaller components of GCSE Language and Literature, such as an introduction to an essay, or a sentence of inference based on a test, or a sentence of evaluation in response to a statement. By practising these skills in short bursts on paper, you can really work to break down some of the barriers students have towards the GCSE papers.

The Home Stretch

5 top tips for preparing students for their English exams

It’s that time of year again: the countdown to exams has begun. Whilst most of us have hit the start of our Easter holidays (thank god!) and are hopefully planning out how to spend the next two weeks resting and recuperating, for me it’s inevitable that I will spend some of that time thinking about my Year 11s and how to get them through the last few weeks – the home stretch – before their exams begin.

In this post, I will share my five top tips for preparing students for their English exams.

Most of these tips relate to revision strategies that you can employ in the classroom to prepare students for their exams. This is something I think is incredibly important this year, considering the amount of learning this cohort has missed due to Covid and how, in many schools, teachers are reporting a huge issue with revision culture at home. It is incredibly difficult to establish a culture of revision at this point in the year, if there is not one established already. This is a battle that, as individual teachers, is very hard to fight. We cannot force our students to revise the subject outside of lesson time. However, what we can do is make the time students spend with us in lesson as impactful and high-leverage as possible.

1. Confidence is key

At this time of year, it’s more important than ever that we invest in building students’ confidence: tell them how impressed you are by what they know; remind them of how much they’ve learned; reflect with them on how far they have come since they started their GCSE journey. Positivity and encouragement can go a long way. From my experience, student confidence is a large part of the battle when it comes to exam season, so I like to spend the few weeks leading up to the exams constantly reminding my students of how proud I am of them. We also can’t assume that students are getting this encouragement at home, so it might just be that their teachers are a vital source of comfort and confidence during this stressful time. They might squirm or roll their eyes but somewhere deep down it will be gradually boosting their confidence and convincing them that they are ready for exam season, despite what they might think.

2. Practice makes permanent

Linking to this idea of the importance of confidence, it is imperative that we prepare students as much as possible for the exam scenario. We need to regularly expose them to exam-style questions in a way that will build both resilience and exam-smart skills. Something I have found really useful for English Literature is what I call ‘exam-drills’. At the start of the lesson, I will give students an exam-style question, a mini-whiteboard, and a pen, and give them ten minutes to independently practice planning an answer to the exam question in a low-stakes environment. I will then circulate the room, identify misconceptions, and address said misconceptions through either some quick-fire feedback or modelling of how I would have approached the question. Depending on the outcome, I will then take the lesson from there. Sometimes, I’ll go completely off-piste from my original lesson plan and invest more time into correcting the errors I have noticed, perhaps by modelling a full written response to the question I gave them. Other times, I’ll give praise and encouragement and then go back to the rest of the lesson I had planned.

The level of independence I insist on during these exam drills very much depends on the needs of the class and the question I have given them. I recently saw Jennifer Webb (@FunkyPedagogy) use the term ‘health struggle’ which I liked. And I feel what make struggle ‘healthy’ very much depends on the makeup of the class. Sometimes, I insist that students work on their own for the full ten minutes, even if that means having a blank board at the end of the time. This can be useful for students that have decent self-esteem in the subject but are clearly not revising as much as they should, and need a bit of a wake-up call to remind them of the gaps they need to fill. I will say things like ‘Remember this feeling of frustration you have now because you don’t remember everything you need to in order to answer this question. Times that by ten, and that’s the feeling you will have in the exam if you don’t do your revision’. Of course, what can be motivating to one class can be demoralising to another. With those classes that are less confident, I will intervene if I think the struggle is becoming ‘unhealthy’ or unproductive, and do more of a reassuring ‘Okay, we clearly have a gap. But that’s okay! Let’s have a look at this together’. Other times, I give students a heads-up of the exam-drill we will be doing the following lesson. This can encourage students to do some revision overnight. This can be particularly useful for classes that need some motivation to revise. Different classes respond to different approaches, but the important thing is that they are routinely being exposed to that exam-style situation so that they have built resilience for the ‘real thing’.

3. List the moments

This is a tip specifically for preparing students for their English Literature exams. Another revision activity I like to use with students is giving them a character, theme or even an exam-style question and getting them to list all the moments in the text that are relevant to that thing. I like to do this on a whiteboard and remind them that, no matter how insignificant the moment might seem, as long as they can explain its relevance to the prompt, it goes on the board. This can kill a few birds with one stone. It can build confidence by reminding students of everything they know about a particular topic. It can become a preliminary stage in the planning process and thus a useful habit to get into for the exam: listing everything that is relevant to the question before cherry-picking the moments that will best prove your line of argument. It can also be used to strengthen knowledge of the structure of the text when you encourage students to, either during the task or retrospectively, list relevant moments in chronological order. Finally, it can build exam resilience by getting students into the habit of getting started straight away, rather than wasting minutes panicking about what they don’t remember. Something I say to students all the time is: it is a waste of time in the exam panicking about what you don’t know or don’t remember – focus on what you do know. This activity can be great for making this thought process habitual for students, even in high-pressure scenarios.

4. Quotations, quotations, quotations

Another Literature-specific tip. And a fairly contentious one at that. I know quotations aren’t the ‘be all and end all’. And I know you do not need exact quotations to write an excellent Literature essay. References to the text count. I know this – I’m an examiner myself. However, what I also know is that learning a select few rich quotations can unlock some beautiful analysis. It can also focus students’ revision and give them confidence when talking about a particular character or theme. For example, my students feel so pleased with themselves when they can use Sheila’s change from the infantile term of address ‘mummy’ to the more distant and mature ‘mother’ as evidence of her progress throughout the play. This is a great example of selective quotations which unlock both ideas and analysis (AO1 and AO2, if we’re talking AQA Literature). A quotation revision activity I find really useful is one that @__codexterous writes about in his blog post here. As the title of the post suggests, all you need is some flashcards and a visualiser to deliver a great lesson which encourages students to make links across the text and look for patterns in choices by the writer. This is one of my favourite revision lessons to use with pupils, and I always find pupils walk away feeling much more confident in providing thoughtful interpretations surrounding the topic of the lesson.

5. Model it

The importance of high-quality models cannot be understated, especially in the lead-up to exams. Yes, students need to be doing more independent practice themselves, but they also need to be continually seeing expert models that they can reflect on and use to further their learning. Every time I give students a model, I walk them through exactly what makes it a good example and get them to annotate the strategies I want them to employ in their own writing. While it can be tempting to pick out all kinds of things that make a model successful, I usually pick one or two things I want to focus on for that lesson. For example, I might specifically focus on how a model uses signposting to clearly navigate through the line of argument, or how sentence stems such as ‘This is consolidated in’ and ‘This is further developed by’ can be used to add more depth and detail to analysis. Getting closer to exams, I like to ask students what they expect to see from a particular model before I give it to them – I get them to explain what they would expect from a model of a particular level. Then we read and annotate where/how the model has done these things. This, I find, encourages metacognition by getting students to reflect on their writing process – if they know what to expect from a high-quality model, they also know what to include in their own writing to make it high quality.

Summary

In sum, there are two vital threads that must underpin every lesson that we spend with students in the run up to their exams: building confidence and resilience; and rehearsing the practical skills that prepare students for the exam situation. It is these two things which will give them the best chances of success when they are experiencing the ‘real thing’ and, while students are unlikely to thank you at the time for relentless ‘exam-drills’ or the countless hours you have spent writing models, they will (if not outwardly then perhaps somewhere deep, deep down…) thank you on results day when they are opening those all-important envelopes, knowing that you did everything you could to support them.

High Leverage Feedback

Principles for effective and efficient feedback to students

Feedback is arguably one of the most important yet most challenging aspects of teaching to master. If I could have back the amount of time I spent as a trainee teacher trying to conquer effective feedback…I might just be able to mark the set of Year 10 assessments that are sitting in my car for their daily trip from school to home and back again.

When it comes to feedback, I’ve tried it all. Lengthy, individualised written comments. Coded marking. Whole-class feedback. DIRT tasks. It took me a good few years to realise that no single type of feedback works for all of us, in all contexts, all of the time. What I have discovered, however, is that there are core principles that we can all apply to ensure that feedback is as high-leverage as possible, no matter the context. This discovery was made through both my own experience in the classroom and by reading Bambrick-Santoyo’s FANTASTIC book ‘Leverage Leadership 2.0’, which completely changed my outlook on feedback. The research and ideas discussed in this book have been transformative to me as a teacher and a leader. So, if there’s anything you find useful throughout this blog post – all credit goes to this book.

What is ‘high leverage’ feedback?

In short, high leverage feedback is feedback that has the greatest impact in the shortest time; it is using feedback to maximum advantage. And there are a set of core principles that can make our feedback as high leverage as possible.

Principle 1: Efficient data gathering

To make a judgement on the performance of a student, we must first gather data. However, there can sometimes be the misconception that data means just figures and numbers, such as scores in a recent assessment. But this is not always the case: data can be observational. Data can be finding patterns and trends based on what you see. And, in fact, it is this observational data which I would argue to be the most rich and useful to the feedback process.

For our data gathering to be effective, it must first be frequent enough. If we only truly observe student performance a few times a year, it is incredibly difficult to coach them to improve. Instead, we may find ourselves merely evaluating: making a judgement on their performance based on a limited data set. And evaluating does not lead to improvement - coaching does.

Now, here’s where the ever-present, number one issue in our profession springs up: time. How can we make more time? The answer is – we can’t. But what we can do is capitalise on the time we already have. We can use live marking and purposeful circulation to make the most of the time students spend in the classroom – gather data while they are working. Not only does this lessen the pressure to spend time gathering data outside of our teaching hours, but it also means we are more likely to be able to respond quickly to misconceptions. Which leads us to principle two…

Principle 2: Immediate responsiveness

Bambrick-Santoyo (2018) suggest that the way to make learning time more efficient is to ‘spend less time on what students already know, and more on what they need’. In other words, it is essential that feedback is delivered in a timely manner so that lesson time can be used to maximum advantage – if we wait to deliver feedback, we are creating a dangerous opportunity for misconceptions to become entrenched.

This is, again, where live marking and feedback become so useful. Circulate the room while students are working; have one-to-one conversations to correct individual errors; deliver whole-class feedback to address widespread errors. Some of the richest feedback discussions I have had have taken place immediately after, or even during, students’ work. This means there is virtually no time wasted between noticing the error and giving the feedback.

Of course, live feedback is not always suitable or possible. Another potential antidote to ‘the time issue’ is sample marking followed by whole-class feedback. We don’t always need to mark every book in depth to get a taste of what the misconceptions/errors are or how improvements can be made. There are, of course, limitations to this method (as with everything) but it is certainly worth a try.

Principle 3: Savvy action setting

Principle three is all about the next step: once you’ve gathered data, when you are responding as immediately as possible, how do you ensure action steps are high leverage?

Savvy action steps consider the following questions:

- Which piece of feedback will allow this student to develop most quickly?

We need to consider the learning trajectory of the pupil/class, and our subject knowledge is imperative here. As subject experts, we need to determine exactly which action needs to come first to make the biggest difference to students’ performance now. To give an English example, students need to be able to articulate what happens in a text and the key ideas before they analyse in detail the choices a writer has made. So I wouldn’t deliver intricate feedback on the impact of the motif of light in ‘A Christmas Carol’ to symbolise Scrooge’s journey to redemption, for example, before I ensure that students can articulate what ‘redemption’ actually is.

- What micro, bitesize action steps can I give to ensure incremental progress?

Something we must remember when giving feedback is cognitive overload. Whilst it might be tempting to want to fix everything all at once – this is impossible. Smaller, bitesize action steps have been proven to be more effective in the feedback process (EEF), and thus we must ensure we aim for incremental and sustainable progress.

- What needs to happen and, more importantly, how does this need to happen?

Once we have decided which piece of feedback will lead to quick and incremental improvement, it is important our action steps are incredibly specific. For example, telling a student they need to make their creative writing more engaging is futile. How will they do this? By embedding a motif to build intrigue? By subtly crafting a mysterious character? We must remember that students are novices. If they knew how to fix their work, they would. We have to coach them by presenting and modelling very specific action steps. Otherwise, it is likely our ‘feedback’ will be fruitless. So, use guided practice to coach students on how to improve, explicitly narrate how to address the error, and then give students time to practise for themselves.

Principle 4: Continual monitoring

In order for our feedback to fully ‘land’ with students, we must continually monitor their work after the feedback has been delivered. It is unlikely that the error or misconception we have addressed will be permanently fixed after just one session of feedback. We must continually monitor whether we are seeing the improvement we hoped to see. We might find we need to simply remind students of the feedback, or praise them when they have put the feedback into action, in order to embed it further. Sometimes, if our feedback hasn’t led to the improvement we hoped, we might need to ‘go back to the drawing board’ and start the cycle again in terms of gathering data and coming to a judgement on what a savvy action step looks like. Regardless, it is imperative we continually monitor so that we can remain responsive and adaptive to emerging needs within our students.

Principle 5: Humans first

The fifth and final principle of effective feedback is to remember that we are dealing with human beings. All humans are fragile and vulnerable – small humans even more so. It is therefore paramount that we deliver feedback with empathy. The Education Endowment Foundation report that it is as important to tell students what they got right as it is to tell them what they got wrong. This, of course, makes sense. What human wants only criticism and not praise? We must also remember that human beings rarely make an effort to do something badly. If students knew how to make their work perfect, they would. So deliver feedback with kindness and empathy.

On the other hand, we should strike a balance between compassion and clarity: don’t let being ‘too kind’ get in the way of being honest. Honest feedback that will ultimately lead to improvement is kind, in the long run.

Teaching the use of a motif in creative writing

If you’ve read my blog post on the motif of birds in ‘Romeo and Juliet’, or in fact read any of my recent tweets, you’ll know that I love a good motif. As I explained in this blog post: ‘The Oxford Dictionary definition of a motif is ‘a dominant or recurring idea in an artistic work’. I like to define it as a recurring image with symbolic significance.’

After teaching students to look for and analyse motifs in the literary works we were studying, such as ‘Romeo and Juliet’ and ‘A Christmas Carol’, I realised that the same method that had unlocked a plethora of insightful analysis and thoughtful interpretations in their study of literature might just be the thing to transform their creative writing too. And I have been so pleased to find it has worked. In fact, ‘worked’ is an understatement – it has transformed their writing.

At Key Stage 4, we teach a structure called ‘Drop, Shift, Zoom, Link’ that we ‘stole with pride’ from someone on Twitter a few years ago (unfortunately I can’t remember who!). I see many variations of this structure taught in different schools, such as ‘Drop, Shift, Zoom in, Zoom out’. The issue was that students were able to use this structure perfectly fine. And it definitely improved their writing by moving them away from a narrative crammed with mind-boggling amounts of action, or a description with pace so slow you struggled to get to the end without yawning. But, whilst their writing had more structure and direction, it was still lacking in…something. A hook, I suppose. Something to build engagement – something to make you want to keep reading. The majority of students were following the set structure well and even attempting to build a convincing character or narrator. But there was just nothing particularly engaging about their work. There was no intrigue, no mystery.

So, I introduced motifs in their creative writing. And I promise this is no exaggeration – it completely rescued their writing. Not only has it utterly stepped up their game in terms of building engagement for the reader, but it has also unlocked a new level of confidence that I didn’t think was possible.

Here’s what I did. I reminded students what a motif was and I explained that we were going to start using them in our own creative writing. The way I explained it was that we would include an important object or person and gradually reveal the significance over the course of our writing. I often refer to the motif as the ‘important something’. I then explained why: to build intrigue and mystery by providing an engaging ‘hook’ in our writing. Next, I explained how we would do this: we would introduce the motif in the ‘Drop’, keeping it vague and curious; then we would mention the motif again in the ‘Shift’, revealing a little bit more about its significance; we would mention it a third time in the ‘Zoom’ paragraph – but only in passing, leaving the reader wanting more; and finally, we would use it in our ‘Link’ to either retain the mystery (forever withholding from the reader the true significance of the motif) or the create an ‘ah-ha!’ or shock moment (eventually revealing its significance).

Of course, the next step was modelling by presenting and then thoroughly dissecting a model which demonstrated the effective use of a motif. All my models can be found in this folder here – ‘Old Man’, ‘Motorbike’, ‘Cobbled Street’ are the best examples. The first one I showed them was the ‘Motorbike’ model, which is a great example of using the to build up to a bit of a shock moment (as long as you’re not opposed to a slightly gruesome ending!) The use of high quality models was, as ever, imperative in this process. Not only was it important for students to understand how to use a motif in their writing, but it was essential to get them to understand why they should use it – because the motif got them hooked into my model answer, just like they wanted their reader to be hooked into their own writing.

Following the studying of the model answers, next came practice. And lots of it. We practiced planning the use of a motif in our writing. Then I would give them feedback and they would make tweaks. Then they would plan again. The next lesson, they would get a new task and practice the process all over again. One thing we learned, through trial and error, is that there is a careful balance to strike between too much and too little focus on the motif. Too much – and you get a piece of writing that appears to be solely about, for example, a battered, old teddy bear and the reader has no idea why. Too little – and the reader doesn’t pick up on the significance, so it just seems like a random detail.

The great thing about students using motifs in their writing is that the motif can stay the same no matter what the task is. This, I have found, has given my students a newfound confidence. In an exam situation, they cannot prepare an answer and then regurgitate it in the exam – we know the dangers of this from the 2022 AQA Language Paper 1 ‘Priest’ debacle – but they can certainly go into the exam with an idea for a motif that they can weave into any task or storyline. For example, one of my students always includes the character’s grandfather’s precious pocket watch, another usually uses a wedding ring. So, no matter what task they are given, they have something they know they can include. They have a starting point, so this has taken away the dreaded feeling of ‘where do I even start?’ that was preventing many students from feeling successful in their creative writing.

Another benefit of teaching motifs in creative writing is that they work no matter what the student’s current writing ability is. From my weakest to my strongest writers, all my students have benefited from including a motif. They can be as creative and experimental as they like. In a recent mock exam, one of my students took inspiration from my ‘Snow Dogs’ model and made their motif a phrase, rather than a ‘thing’, and wove the sentence ‘Some things in life never change’ into each section of her writing. It worked beautifully.

So, if you’re looking for a way to get your students to add a bit of extra something to their writing – to build intrigue and engagement and get them really thinking about the significance of subtle details – try teaching them to use a motif. I hope you find it as transformative as I have!

5 ways we ensure success with anthology poetry

The poetry anthology is arguably one of the hardest components of the AQA GCSE Literature qualification. Between having to learn and recall a whopping 15 poems prior to the exam and then having to juggle the analysis of two texts simultaneously in the exam, the anthology poetry question asks a lot of our 16-year-old students.

Here are 5 strategies we use to ensure students’ success in this component, complete with links to loads of free resources. We teach the ‘Power and Conflict’ cluster but the resources are easily adaptable.

1. Explicit teaching of ‘Big Ideas’

We coach students to compare the poems through similar ‘Big Ideas’ that they reflect. We explicitly teach Big Ideas such as ‘Nature is more powerful than man’ and ‘Identity can be complex and confusing’ that students then use as a basis for comparison in their essays. A full list of our Big Ideas can be found here on our Topic Guide. We begin teaching these in Year 10 and move into the nuances of each one in Year 11. We find these give students much more confidence in planning a comparison and they also reduce the likelihood of students just ‘feature spotting’ in the exam, which often leads to arbitrary analysis and comparison (eg. ‘Both poets use a metaphor…’).

2. Planning sheet

As mentioned, the Big Ideas then become the basis for the comparative essay. From Year 10, we teach students to use this sheet when planning a poetry essay.

It works an absolute treat. Students are taught to explore row by row (rather than column by column) to give ample opportunity for comparison. The Big Ideas in the centre of the plan are used to form the introduction but also the topic sentences of each analytical paragraph. We start off with really detailed plans: each box will be crammed full of ideas, references and analysis. By the time we get to the exam, students are confident enough to just put the key components in the plan, namely the Big Ideas and the quotations/methods that facilitate analysis/exploration of these ideas. Below is an example of a student who used this approach in his GCSE exam last academic year. He started the year on a Grade 3 in Literature and ended up with a Grade 6 overall. On this question, he scored 20/30 for a ‘clear’ response. He reported later that he struggled to think of a reference for one of the boxes but it came to him later: he knew that the plan needed to be quick and efficient, just enough to give him a focused ‘line of argument’ for his essay. His full essay and two other marked scripts from 2022 can be found here.

3. Model answers

Our Year 11s sit fortnightly ‘Big Writes’ in which they practise responding to exam-style questions. Before each of these, we show students model essays that demonstrate the skills we want them to mirror. We talk through each model carefully, focusing initially on how the essay is constructed with the Big Ideas at the centre as the basis for comparison. Seeing high-quality models and then replicating their style and approach is vital for GCSE success. Here is a bank of 10 ‘Power and Conflict’ model essays that we use/adapt depending on the class.

4. ‘Why that method’ sheets

In a previous blog post, I explained how we developed ‘Why that method’ sheets to improve students’ analysis and reduce the amount of vague, unspecific comments on the impact of methods. In teaching anthology poetry, we make most use of the general ‘Why that method’ sheet (which includes the most common language methods like metaphors, personification, juxtaposition) and also the ‘Why that poetic method’ sheet, which is obviously specific to poetry features. All of our sheets are saved here.

5. Strategic ‘Do Now’ tasks

As mentioned at the start of this post, one of the most difficult aspects of the poetry anthology component is the requirement to learn such a large number of poems and be able to recall details about them in the exam. As we all know, retrieval practice is essential to improving students’ recall and embedding knowledge into long term memory. We do retrieval practice every day through our strategic ‘5-a-day’ tasks. We use common misconceptions to inform what we want students to practise in the first 10 minutes of every lesson. With anthology poetry, we know that the following are imperative: understanding the Big Ideas, recalling some key references/quotations, clear analysis of the methods used. Thus, our poetry 5-a-days include questions that require: recall of Big Ideas, recall of quotations (usually through cloze activities), and analysis of these quotations using the ‘Why that method’ sheets, such as the one below:

A full explanation of how we use our 5-a-days, along with examples, can be found in this blog post.

Bards of a feather…

The motif of birds in Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’

Motifs have quickly become one of my favourite methods to explore when teaching literature at Key Stage 4. I love the fact that they give students confidence by enabling them to return to the same method multiple times throughout a text. I love the fact that you can unpick different layers of meaning over time, with each exploration unlocking a new realm of interpretation. I love that they encourage students to make connections between different parts of a text, allowing for discussions around structure as well as language. I love that, once understood, they are a useful tool for students to use when crafting their own writing.

This summer, I delved into Pryke and Staniforth’s wonderful ‘Ready to Teach: A Christmas Carol’ (side note, I am PRAYING for a ‘RTT: Romeo and Juliet’ in the near future) and was delighted to learn more about the numerous motifs employed by Dickens: light and dark, thresholds, eyes. These motifs have become a staple in my teaching of ‘A Christmas Carol’ and have aided some of my weakest KS4 students to feel confident in their analysis of the text. But still, my favourite motif to explore is Shakespeare’s motif of birds in ‘Romeo and Juliet’. It helps that this is my most beloved GCSE text anyway. But I love teaching the motif of birds most of all.

What is a motif?

The Oxford Dictionary definition of a motif is ‘a dominant or recurring idea in an artistic work’. I like to define it as a recurring image with symbolic significance. I find this definition is easier for students to grasp: they know to look for an image (something visual) that has deeper meaning and is mentioned multiple times. We teach symbolism in KS3, starting with symbolism in Dystopian fiction (such as light and dark imagery to symbolise rebellion in Bradbury’s ‘The Pedestrian’) and then build to exploring motifs at KS4. The journey from symbol to motif is a natural progression.

The motif of light and dark in ‘Romeo and Juliet’

Perhaps the most prominent motif to explore in Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’ is the motif of light and dark (or daytime and night-time). As well as facilitating links and embedding understanding of the use of the same method in ‘A Christmas Carol’ and many other texts, there is lots to unpack with the motif of light and dark. One of my favourite analytical discussions to have is about this motif and ideas of safety versus danger. Whilst the rest of the world typically associate light with daytime and thus with safety, Romeo and Juliet implicitly (and often even explicitly) associate light with danger instead (Act 3 Scene 5, Romeo: More light and light it grows: more dark and dark our woes). Shakespeare uses this to place Romeo and Juliet at odds with the rest of society, representing both their rebellion and their duplicitousness. The motif of light can be seen to symbolise exposure – thus representing the danger of the young couple’s secret love affair being discovered. I also like to debate whether the motif of light and dark symbolises Romeo and Juliet’s inability to co-exist (it is impossible for it to be both day and night) or their necessity to co-exist (how do we understand what light is, without darkness?)

Another fruitful exploration of light versus darkness can be had in relation to Romeo’s emotional journey throughout the play, from his melancholy over Rosaline’s unrequited love (Act 1 Scene 1, Romeo: bright smoke, cold fire, sick health and Love is a smoke raised with the fume of sighs) to his instant transformation upon seeing Juliet for the first time at the Capulet ball (Act 1 Scene 5, Romeo: She doth teach the torches to burn bright) to his implication that Juliet has become the centre of his universe and his sole benefactor of happiness in the ‘balcony scene’ (Act 2 Scene 2, Romeo: Juliet is the sun).

The motif of birds: ideas of freedom and restriction

Regardless, the motif of birds remains my favourite method to explore in ‘Romeo and Juliet’. Exploration of this motif unlocks a plethora of different interpretations and connections, which I find productive in classes of all attainment levels.

The interpretation I usually explore first is the use of the motif of birds to connote ideas around freedom or restriction. I guide my class to consider this first of all in Act 1 Scene 1, Romeo’s hopeless profession of love for Rosaline to Benvolio. Romeo’s use of the oxymoron ‘feather of lead’ is the perfect example of his confusion over Rosaline and his supposed ‘love’ for her: how can love, which is supposed to bring freedom and liberation (represented in ‘feather’) be so burdensome and oppressive (represented in ‘lead’). Romeo is like a bird trapped in a cage, forever taunted by the unreachable beauty of Rosaline who chooses ‘chastity’ over Romeo’s ‘loving terms’, ‘assailing eyes’ and ‘saint-seducing gold’. Through this we learn that love, when unreturned or disingenuous (depending on how you view Romeo at this point in the play… I usually lean towards the latter), is something that brings feelings of restriction and limitation.

The use of bird imagery to symbolise restriction can be returned to in other parts of the play. Juliet’s labelling of Romeo as a ‘dove-feather’d raven’ in Act 3 Scene 2, for example, could be argued to symbolise her feelings of helplessness at being irrevocably tethered to a man who has proven traitorous by murdering her cousin, Tybalt.

Elsewhere, the motif of birds can be seen to symbolise the opposite idea: freedom. When Romeo happens upon Juliet in Act 1 Scene 5, he immediately labels her a ‘snowy dove trooping with crows’. The juxtaposition between this and ‘feather of lead’ potentially symbolises Romeo’s newfound liberation after having discovered ‘true’ love. This is reinforced in Act 2 Scene 2 when Romeo describes Juliet as a ‘winged messenger of heaven’ – a reference to angels, certainly, but with an unmistakable nod to bird imagery with ‘winged’ – and later responds to Juliet’s question of ‘How camest thou hither’ with ‘With love’s light wings did I o’er-perch these walls’. Here, the bird motif once again evokes images of freedom but potentially to a new level due to the implication that love has not only released Romeo from his emotional imprisonment but has also given him a super-human ability to over-perch ‘stony limits’ (a testament to his enduring and, in my opinion, infuriating idealism).

We also see a potential association between birds and freedom with Juliet’s language in Act 2 Scene 2, as she wishes for ‘a falconer’s voice to lure this tassel-gentle back again!’ Juliet’s wish to be a ‘falconer’ to ‘lure’ her peregrine falcon (Romeo) back to her reveals her overwhelming desire for power. I like to consider, here, the interpretation that part of what makes Romeo so appealing to Juliet is the fact he represents the possibility for her to escape the prison of her family and allows her to experiment with her own power (something Romeo somewhat manipulatively establishes in Act 1 Scene 5 by branding Juliet a ‘shrine’ and himself a ‘pilgrim’). The irony, though, is that Juliet’s freedom and power comes at the expense of Romeo’s: he must become restricted and powerless, like a trained falcon obeying the commands of its handler.

This dichotomy between freedom and restriction is further developed in Act 3 Scene 5, in which the bird motif is used once again in a power-play between the young lovers. Following their wedding night, Juliet claims ‘It is the nightingale, and not the lark, that pierced the fearful hollow of thine ear’, attempting to convince Romeo he is safe to stay longer on Capulet grounds whilst it is ‘not yet near day’ and thus they are still protected by it being night-time (a delightful multi-motif here, with the intersection of bird imagery and light/dark imagery). For once, Romeo sensibly assures Juliet ‘It was the lark, the herald of the morn’ and that he must ‘be gone and live’ lest he ‘stay and die’. Yet Juliet, drunk on love and her newfound power, continues to convince Romeo he can hear the ‘nightingale’. The nightingale as a symbol of safety (due to its association with night-time and thus secrecy and concealment) is also representative of Juliet’s recently discovered power over Romeo. In turn, the nightingale becomes a symbol of Juliet’s liberation at the expense of Romeo’s entrapment. This is consolidated when Romeo relinquishes all power to Juliet and finally agrees that ‘it is not the lark’, only to have Juliet reverse her decision and claim ‘It is the lark’ and that Romeo needs to ‘be gone’. This evidences that Juliet has become the skilled ‘falconer’ she wished to be in Act 2 Scene 2, having acquired the skill to have Romeo satisfy her every whim.

The motif of birds: further interpretations

If I’ve held your attention this far – I’m incredibly grateful. There are a wealth of further interpretations of the bird motif that I could spend hours (nay, days!) writing about. But, alas, we are teachers and one we are rarely afforded is time. So I will make this next section brief but (hopefully) nevertheless useful.

The motif of birds may also be used to explore ideas around impossibility and extraordinary power (such as Act 2 Scene 2, Romeo: with love’s light wings and winged messenger) revealing Romeo’s seemingly unshakable belief that his feelings for Juliet will provide him with power no human could otherwise dream of (potentially also linked to the feelings of liberation that Juliet has unlocked for him). One may also choose to explore historical associations with particular birds, such as the associations between: doves and peace or purity (Act 1 Scene 5, Romeo: so shows a snowy dove) ; ravens and evil or the supernatural (Act 3 Scene 2, Juliet: dove feather’d raven); crows and danger or pests (Act 1 Scene 2, Benvolio: I will make thy swan a crow and Act 1 Scene 5, Romeo: trooping with crows). These associations prove a rich vein not only in ‘Romeo and Juliet’ but also in many of Shakespeare’s other works, especially ‘Macbeth’ (Matt Lynch has delivered a BRILLIANT presentation on the motif of birds in Macbeth which is available on LitDrive).

Summary

If you teach ‘Romeo and Juliet’, whether it be at KS3 and KS4, the motif of birds proves a worthwhile method to unpack with any class. Motifs in general, can be used to explore an abundance of potential analytical interpretations. Whilst ideas around freedom, restriction and power can be particularly useful considerations, the possibilities are potentially endless.

_____________________________________________________________________________

A final note

This is my first post going into so much depth on an aspect of subject knowledge. It made me particularly nervous to post this considering this play is so close to my heart and I have, until now, never considered my novice self to have much to offer on the subject. I hope you find it useful in some way. If you have any tips, feedback or (I should be so lucky!) requests for further explorations of ‘Romeo and Juliet’, please feel free to let me know on Twitter.

I must also give @JessCappers ALL the credit for the clever title of this post. And thanks to everyone else who replied to my Tweet requesting advice on my language choice.

Strategic Do Now Tasks

How we make the start of every lesson as impactful as possible

Do Now tasks have been common practice in most subjects in most schools since I began teaching. It makes sense to begin with an introductory task before the ‘main’ part of the lesson begins. Around five years ago, we introduced ‘5-a-day’ tasks as our Do Nows in English – an idea I saw shared on Twitter around the same time (if I could remember who to credit the original idea to, I would! I do know that @Mathew_Lynch44 has done some great work on 5-a-days). Our Do Nows became five questions that pupils would independently answer in their books at the start of the lesson to assess what they could recall from the previous lesson or few lessons.

For many years, we used our 5-a-day tasks for two main reasons: to settle students on entry and to activate prior knowledge. And for many years, this worked for us: the 5-a-days were doing their job. This was until we got some worrying mid-year data and decided we needed to go back to the drawing board and consider how to use our lesson time more effectively, especially as revision culture outside of school was rocky. We needed to make the most of every minute that students were in the classroom. So, after some in-depth discussions with my team, we realised that we were missing a vital opportunity with our Do Now tasks. To make our 5-a-days as impactful as possible, they needed to become a form of data-informed intervention. The teacher would then assess, at the beginning of every lesson, whether or not these skills were developing and address any misconceptions that were arising before they became entrenched.

We spent some time deliberating what we thought students were struggling with and what skills they needed to practice, and we came up with a common ‘formula’ for the type of questions that should be included on a 5-a-day. Rather than just any five questions to essentially fill the time, the questions needed to become much more strategic. This resulted in the following guidance which we shared with the team:

KS3 guidance

KS4 Literature guidance

KS4 Language guidance

Teachers were expected to use the guidance to amend or write their own 5-a-day tasks for their classes based on the common misconceptions and areas of need within the class or year group, informed by our data analysis. For example, in Year 8 we were noticing repeated issues with the misuse of semi-colons, so this became the focus for Question 3 - the punctuation-based question. In Year 11, we knew students were struggling to recall quotations, so we made Question 2 for Literature lessons a cloze activity based on quotation recall.

For a while, this worked well. These Do Nows were definitely more thought-through and we noticed an improvement in the skills practised during the 5-a-days. However, like with most things, after a few terms we realised that we needed further adaptations based on new areas for development that had arisen. This is probably the best thing about our 5-a-days: they are adaptive and flexible according to what our students need.

For example, in our November mocks with last year’s Year 11 cohort, we noticed a real issue with the analysis of language methods. Essentially, the confusion between inference and analysis – vague statements made about what a method ‘suggested’ rather than a specific analysis of what THAT particular method actually did. We produced a scaffolded help-sheet to develop students’ analysis skills (explained my earlier post ‘Improving Analysis’) which made a huge difference, but importantly we also practised refining analysis skills through the 5-a-days – every single lesson. We began including a quotation at the top of the slide, and then making the five Do Now questions primarily analysis of said quotation. See example below:

Amended KS4 example - Literature

This process worked really well. We implemented it for the Year 10 cohort at the time as well – who are now in Year 11, and are already a step ahead of the previous cohort when analysing the impact of methods. I’m sure at the next round of data collection we will notice new trends, and we will undoubtedly meet to discuss and strategise how to fix them. But this is what makes our 5-a-days so impactful: they are data-informed, they are adaptive, they are strategic. Essentially, students are completing around ten minutes of assessment feedback and improvement every lesson.

No matter what your current approach to Do Now tasks in your own departments and classrooms, a reflection on whether they are as strategic as you need them to be could be really beneficial – it certainly was for us.

Improving analysis

A resource dedicated to improving specificity and detail in students’ analysis

Something we have noticed as a repeated issue in students' work is them labelling a language method, then just doing inference, and thinking this counts as analysis, such as 'The writer uses a metaphor which suggests...'.

I had SO many feedback discussions with students: but why THAT method? If the writer just wanted to suggest Ozymandias was destructive, why not just say he was? Why instead use a semantic field of destruction? We seemed to go round in circles.

Students weren't explaining why THAT particular method had been used. This was limiting the clarity and precision of their analysis, in both Language and Literature. After much discussion with my wonderful second in department, we came up with a resource - aptly named the 'Why that method' sheet.

The sheet (snippet below) gives students phrases they can use to analyse the specific impact of particular methods. The fact that it puts these phrases in a sentence structure for them is doubly useful.

This has completely transformed their analysis. We have so many more students achieving 'clear' analysis because they can be specific about what particular methods are used for. They use this sheet almost every lesson - in both Language and Literature - and it has become a dedicated part of our ‘5-a-day’ retrieval practice at the start of each lesson.

It also has space on the back for discovery of potential new methods and impacts. We now find students can confidently explain that repetition creates a continual reminder of something, or creates the idea that something is inescapable, rather than always saying 'The repetition suggests that...'

This resource is one of the most useful things we have done to improve students’ analysis and we have found it impactful in all year groups - we are moving on to adapted versions for KS3 students as well. We have different sheets for poetry, structure, non-fiction methods. All of them can be found at this link here.

Curriculum planning: starting with the end

How to use backwards planning to design a secondary English curriculum

If you are contemplating where to begin with your curriculum design, a great way to start is to begin with the end goal in mind. What do you want your students to know, what do you want your students to be able to do, and where do you want students to be by the end of the curriculum journey? In other words, begin by planning out the overall objectives of your curriculum. You can then work backwards from here: in order to reach this end point, where do students need to be by the end of the term, the half-term, the week, the lesson? Moving on from this, your curriculum planning becomes more specific and detailed, moving from the ‘what’ questions to the ‘how’ questions: how are you going to teach students this knowledge or this skill and ensure they remember it; how are you going to ensure they reach the endpoint you have specified?

This process is often referred to as ‘backwards planning’.

According to Wiggins and McTighe (1998), there are three stages of effective backwards planning: decide on the desired outcome; decide on acceptable evidence; plan learning experiences and instruction. These stages apply not just to how we would plan an entire curriculum, but also how we would plan the smaller components within said curriculum, for example a unit of work or an individual lesson.

Stage 1: Deciding on the desired outcome

The ultimate desired outcome for all students of English (in all schools and at all key stages) should centre around developing a knowledgeable and effective literary critic who can understand the power of language to shape the world around us: how we present ourselves, how we interact with others, how we document our lives and our experiences in the written and spoken word.

When planning our curriculum, we need to decide what an effective literary critic looks like to us: what knowledge and skills should students have by the end of the 5-year journey that would signpost them as a successful critic of literature? For example, you might decide that students should be able to: read an unseen text and respond with a perceptive understanding; find specific evidence and examples to support their viewpoint; deconstruct the choices made by a writer and consider the potential impact of these choices. Deciding on the desired skills of an effective literary critic is a useful starting point for curriculum planning.

I would advise avoiding outcomes that concentrate on what you want students to know by the end of their study. This is difficult to check or measure and can therefore be a difficult end-goal to work towards. Instead, it is better to focus on what you want students to be able to do by the end of their study. This ensures that your end goals are measurable and focused on what pupils can independently produce, which can thus be appropriately assessed. This therefore makes it easier to decide and plan more minute criteria that will inform you of whether students are acquiring the desired skills/knowledge throughout their period of study.

Wiggins and McTighe (1998) also suggest a series of useful questions that we may consider in this stage of our planning: what should students encounter; what should students master; what should students retain? For example, you may determine that you want your students to: encounter the text ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’; master the skill of identifying language used by Shakespeare to indicate power dynamics between men and women within the play; and retain ideas around patriarchy and the use of language to display power. It is the latter which is arguably the most important component to consider: what is the enduring understanding that it is imperative our students retain in order to be successful later on?

As an additional advisory note, it is also imperative at KS3 that we avoid perceiving desired outcomes at KS3 in the prescriptive way that is unfortunately common in secondary schools – as inextricably linked with GCSE outcomes. A KS3 curriculum should not be about merely ‘preparing students for KS4’. Instead, ask yourself: what should a successful student of English be able to independently do by the end of Key Stage 3?

Stage 2: Deciding on acceptable evidence

The second stage of backwards planning asks the curriculum planner to consider: what are you going to accept as evidence that pupils have acquired the knowledge you wanted them to, or developed the skill you intended? What evidence will you accept that students both know and remember what they need in order to move on?

Once you have decided on the desired outcome(s) of your curriculum, you must ask yourself: how will I know that students are on the way to achieving these outcomes? Wiggins and McTighe (1998) press the importance of the acceptable evidence directly matching with the desired outcome: in order to avoid frustration and inefficiency, it is imperative that the assessment directly reflects the learning goals.

It is also imperative at this stage to consider the importance of independent practice. Students must be given the opportunity to independently apply the knowledge and skills they have gained. The only way for pupils to really hone their skills and confidently embed their knowledge is to practice independently with the chance to make mistakes, work through these mistakes, and eventually improve.

Stage 3: Plan learning experiences and instruction

The final stage is when the ‘finer details’ begin to be ironed out. If Stages 1 and 2 contemplate the ‘what’, Stage 3 considers the ‘how’: how will the desired knowledge and skills be taught? At this stage, one must explore which strategies will best equip students with what they need to know and which tasks or activities will give students the opportunity to experiment with their new knowledge and skills.

A common error made in the design of curriculums, units of work, or even individual lessons is deciding on what you want pupils to do before you decide what you want them to be able to do. To leave the planning of learning experiences and instruction until Stage 3 is to ensure that lessons, activities or tasks are not merely time-fillers, they always explicitly move students towards the ultimate desired outcome.

Anticipating difficulty

An additional principle of effective backwards planning which is not originally discussed by Wiggins and McTighe (1998) but I feel is nevertheless essential is anticipating difficulty. When initiating your curriculum planning, you should consider the following questions:

Where do you anticipate that students will encounter difficulty reaching the desired outcome?

What gaps might students have that need filling, or what misconceptions might need addressing, in order for them to successfully reach the end goal?

Whilst deciding on an end-goal is important, taking stock of your starting point is also vital, and we must be realistic here, focusing not on what pupils should know but instead on what they likely do know at the start of their journey. This is perhaps particularly important following school closures and the widespread impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ample time and consideration must be put into what knowledge and skills students may not have mastered that they otherwise may have, under ‘usual’ circumstances.

In anticipating difficulty and using this to plan an effective curriculum, communication is key. Talk with your KS2 feeder schools about how you can avoid repetition (a common complaint is that the Year 7 curriculum is not challenging enough due to secondary educators lacking knowledge of KS2 content) and how you can address misconceptions that KS2 teachers may have noticed in their students but not had the time or resources to address. Talk with your team and draw on their experiences: what knowledge/skills do pupils often struggle to master? What experience do they have with effective ways to address these difficulties? These conversations are incredibly useful to ensuring you have anticipated difficulty.

The concept of anticipating difficulty is sometimes misinterpreted as being at odds with the notion of high challenge within a KS3 curriculum. This must not be misunderstood. All passionate KS3 teachers and leaders want to develop an ambitious, challenging and rigorous curriculum – anticipating difficulty does not contradict this. Put simply: if we don’t acknowledge the misconceptions or gaps that students have or the difficulty that they might face/are facing in reaching the end goal, this ambition (both yours and theirs) will be futile. This is about being reflective practitioners who focus not on what should be but on what is, thus delivering a curriculum that serves its students well because it acknowledges the reality of their educational experiences thus far, and their likely experiences in the near future.

Building a mastery curriculum

Developing depth and nuance using ‘Core Knowledge Overviews’

Developing depth and nuance using ‘Core Knowledge Overviews’

One of my biggest feats as a new Head of Department was developing a curriculum that ‘ticked all the boxes’: sufficient challenge, a balance of breadth and depth, ambition, suitability for our students and context…the list goes on. When I began working at my school as a trainee, we had nothing but some downloaded schemes off TES which ticked none of the aforementioned boxes and which were limited in their ability to move pupils forward, as they were mostly randomly strung together and had no continuation between them. Everyone was planning independently, the wheel was being reinvented (and reinvented, and reinvented, and reinvented…); our curriculum barely existed at all.

When we then became part of a large academy chain, we were really lucky in being provided with tonnes of high-quality resources and example curriculum maps. We had a lot of guidance from some extremely experienced and knowledgeable specialists. But we were keen to make our curriculum just that – OUR curriculum. We really started from the ground up, and this took a lot of care and consideration.

We planned backwards from where we wanted pupils to end up (see my blog post here on backwards planning) and then worked out how we would get them there. I am blessed with an EXCELLENT team of specialists who all got involved and were eager to make our curriculum ambitious and effective. We developed outlines of what we wanted to teach, to who, and when, and then began producing lesson resources for each year group and each unit.

It's taken us years to get to a place where we are happy with our curriculum – and we’re still not done. We’ll never be done! But one of the best and most useful things we did was introduce our ‘Core Knowledge Overviews’. These have been essential in developing our mastery curriculum.

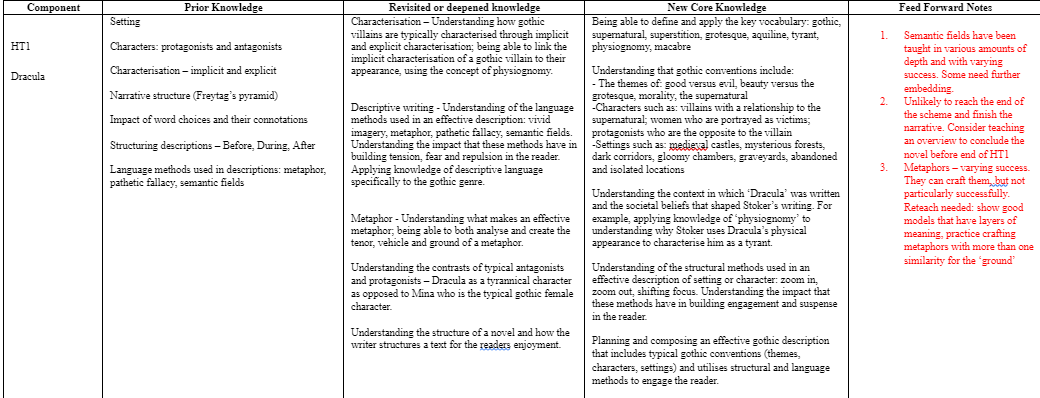

Our Core Knowledge Overviews plot out each scheme of work in each year group and explicitly detail the prior, revisited or deepened, and new knowledge we teach in each scheme. Of course, our Medium-Term Plans and the resources within the schemes themselves are much more detailed and complex – but these documents just detail the CORE knowledge. For these overviews, less is more. Below is an excerpt from our overview for Year 8 half-term one.

I should note here that we didn’t come up with the original idea of a core overview ourselves – we saw an example from another subject in another school (I genuinely cannot remember where) and we adopted and adapted to fit what we needed. As always, I’m eternally grateful to the kindness of those in our profession who generously share their resources!

Our Core Knowledge Overviews are so vital because they help everyone (me, my team, new staff, non-specialists involved in the department) understand and articulate exactly WHY we teach what we do and how it builds over the five years. You will notice that the same snippets of knowledge appear again and again – building in depth and nuance over time.

For example, you can see how students’ understanding of different types of characters develops over the five year curriculum – starting with relatively simple protagonists and antagonists in Year 7 in ‘Wolves of Willoughby Chase’, to the specifics of gothic villains in Year 8 in ‘Dracula’, to the nuance of tragic heroes in Year 9 in ‘The Crucible’ and ‘King Lear’. By Year 11, students understand that most characters (and, in fact, most human beings in general) cannot simply be characterised as either heroes or villains, protagonists or antagonists. We are all incredibly complex, multi-faceted, capable of both good and evil (take, for example, our complicated anti-hero, Scrooge, in ‘A Christmas Carol’). In developing this nuanced understanding, students are learning the complexities of the human condition which, I would argue, is one of the most important aspects of an English curriculum’s intent.

We use the final column of the Core Knowledge Overviews to continuously reflect on our curriculum and our teaching, discuss our strengths and areas for development, and make notes of what needs to ‘feed-forward’ as we continue teaching. Every few weeks in our department meeting/CPD, we pick a year group to focus on, look at each other’s books, and discuss what we need to do moving forward to further embed and secure the core knowledge. This ensures our teaching is both laser-focused and adaptive – which is so important to pupil progress.

Our Core Knowledge Overviews can be found at this link here. They are, of course, a work in progress and (like most things) will never be fully ‘finished’. But they are an incredibly worthwhile investment and have been instrumental in developing our mastery curriculum – both in theory and in practice.